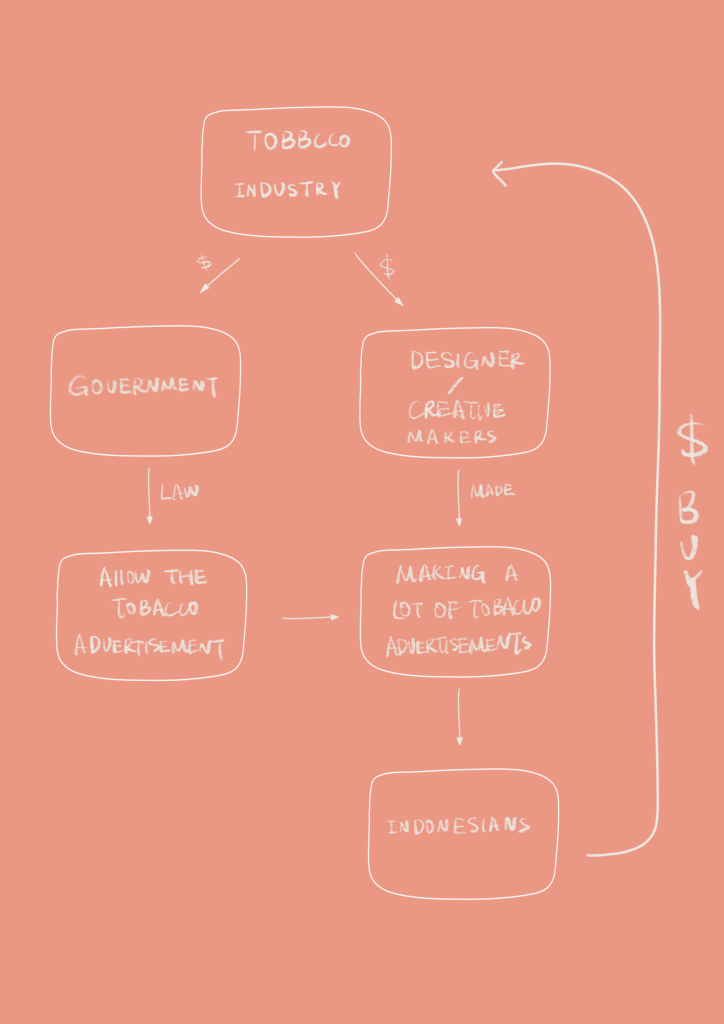

Tobacco companies have enormous political and financial influence in Indonesia and are the third-largest source of revenue for the government (Reynolds, 1999). So, in Indonesia, tobacco companies have few policy restrictions. The number of young Indonesians is growing in recent years, with more than 45% Indonesians are under the age of 20. So, tobacco companies began to encourage young people to smoke by advertising and sponsoring large events. Designers and creative culture makers, such as artists, social media influencers or entrepreneurs, play a vital promotional role. They design the brand culture, packaging and advertising of cigarettes and spread them on social media and the Internet. As the second-largest Indonesian tobacco company, Sampoerna, rice: “The relevance to the consumer of a brand’s image and lifestyle will be the defining characteristic for success in the years to come.” (Reynolds, 1999) Designers associate cigarettes with lifestyle and personal characteristic, for example, strong masculinity and individuality are the predominant themes of cigarette advertising in Indonesia. And some ads, using highly successful men as examples, suggest that people can use cigarettes to attract women and become rich. Those tobacco advertisements deliver very misleading content – smoking means success, charming, courage, and popularity. These contents have great appeal to children and teenagers. Therefore, Advertising has had a very real impact on increasing the number of Indonesian smokers. Especially among young people, they are very concerned about their identity, so they are identified as the main contributors to the future profits of Indonesian tobacco companies.

Because of the huge profits that advertising can bring, tobacco companies are putting more emphasis on investing in designers and producers of creative cultures. Cigarette companies sponsor almost all of the country’s concerts and sports events. (Dhumieres, 2019) All major Indonesian tobacco companies sponsor sporting events. (Reynolds, 1999) Tobacco billboards are prominently displayed and frequently changed in Yogyakarta. Yogyakarta government directly gets many benefits from cigarette revenues and the “social contribution” provided by the tobacco industry. Most of the small newsstands and shops in Yogyakarta are covered in tobacco advertising because tobacco companies offer cash payments and artwork to small shop owners. (Nichter et al., 2008) At the same time, cigarette companies sponsor many design companies and cultural and sports activities to obtain the support of designers and artists.

In Indonesia, it is difficult for designers and creatives to get financial assistance from the government or private sponsorship. However, tobacco companies serve them by controlling the design industry economically. But there is no denying that designers and creatives play a vital role in the spread of information on social media and the web. If the government can support designers, let them participate in anti-tobacco activities, I believe it can achieve good results.

Reflection:

Dhumieres, M. 2019, The number of children smoking in Indonesia is getting out of control, Public Radio International. viewed 18 December 2019, <https://www.pri.org/stories/number-children-smoking-indonesia-getting-out-control>.

Nichter, M., Padmawati, S., Danardono, M., Ng, N., Prabandari, Y. and Nichter, M. 2008, Reading culture from tobacco advertisements in Indonesia, Tobacco Control, vol 18, no 2, pp.98-107,.REYNOLDS, C. 1999, Tobacco advertising in Indonesia: “the defining characteristics for success”, Tobacco Control, vol 8, no 1, pp.85-88,.

Reynolds, C. 1999, Tobacco advertising in Indonesia: “the defining characteristics for success”, Tobacco Control, vol 8, no 1, pp.85-88,.