Traces of tobacco exist in every crevice of Ambon: used cigarette butts discarded on the sidewalk; empty cigarette packets floating in the river; Ambonese men smoking along the streets; and the smell of tobacco wafting through the air – all constant reminders of tobacco’s long history in Indonesia, rich with cultural symbolism and associations that existed before the advent of advertising (Reynolds 1999). Perhaps the most jarring, and arguably the most noticeable, aspect of tobacco culture is the plethora of tobacco advertising that densely saturates the Indonesian landscape.

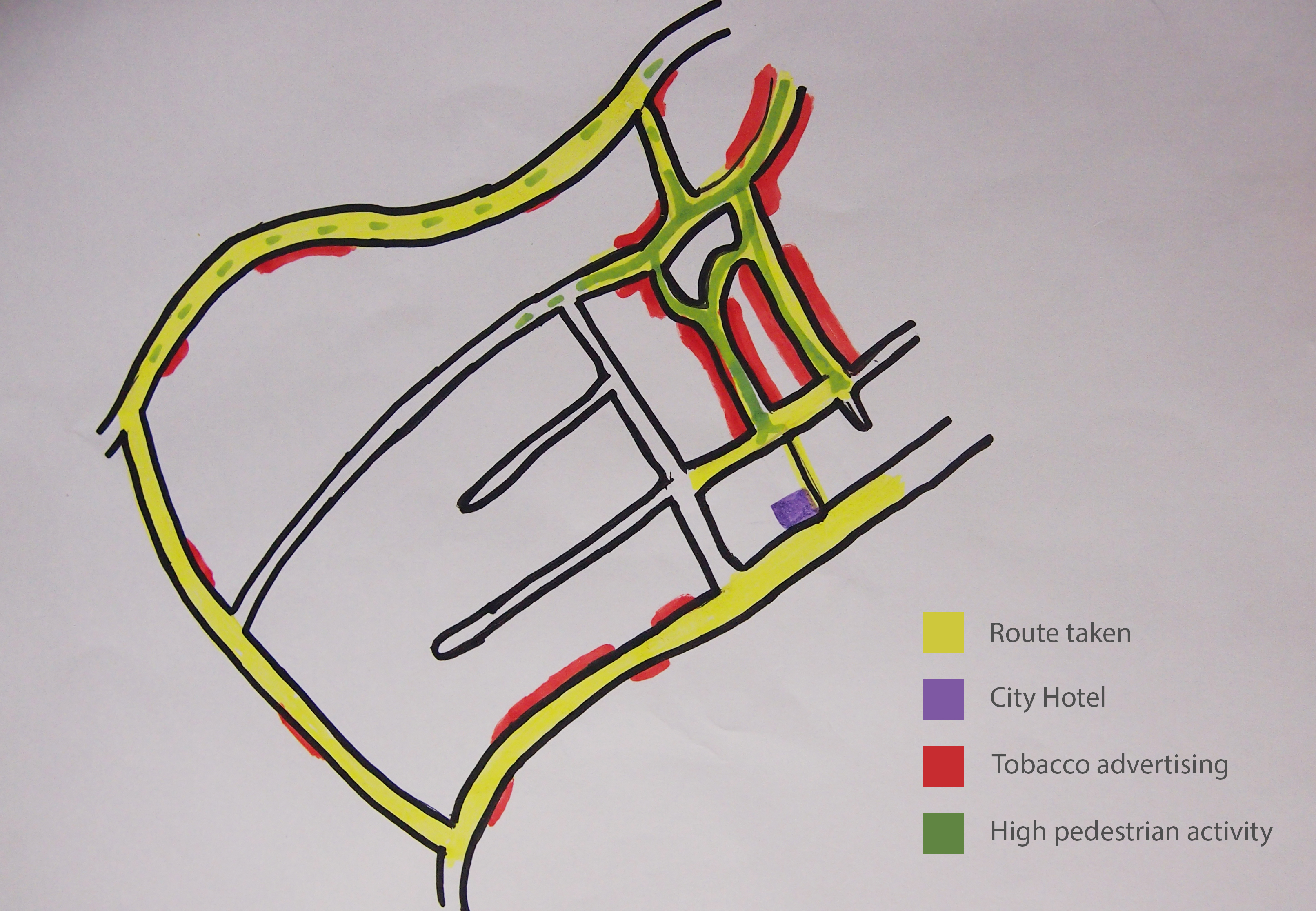

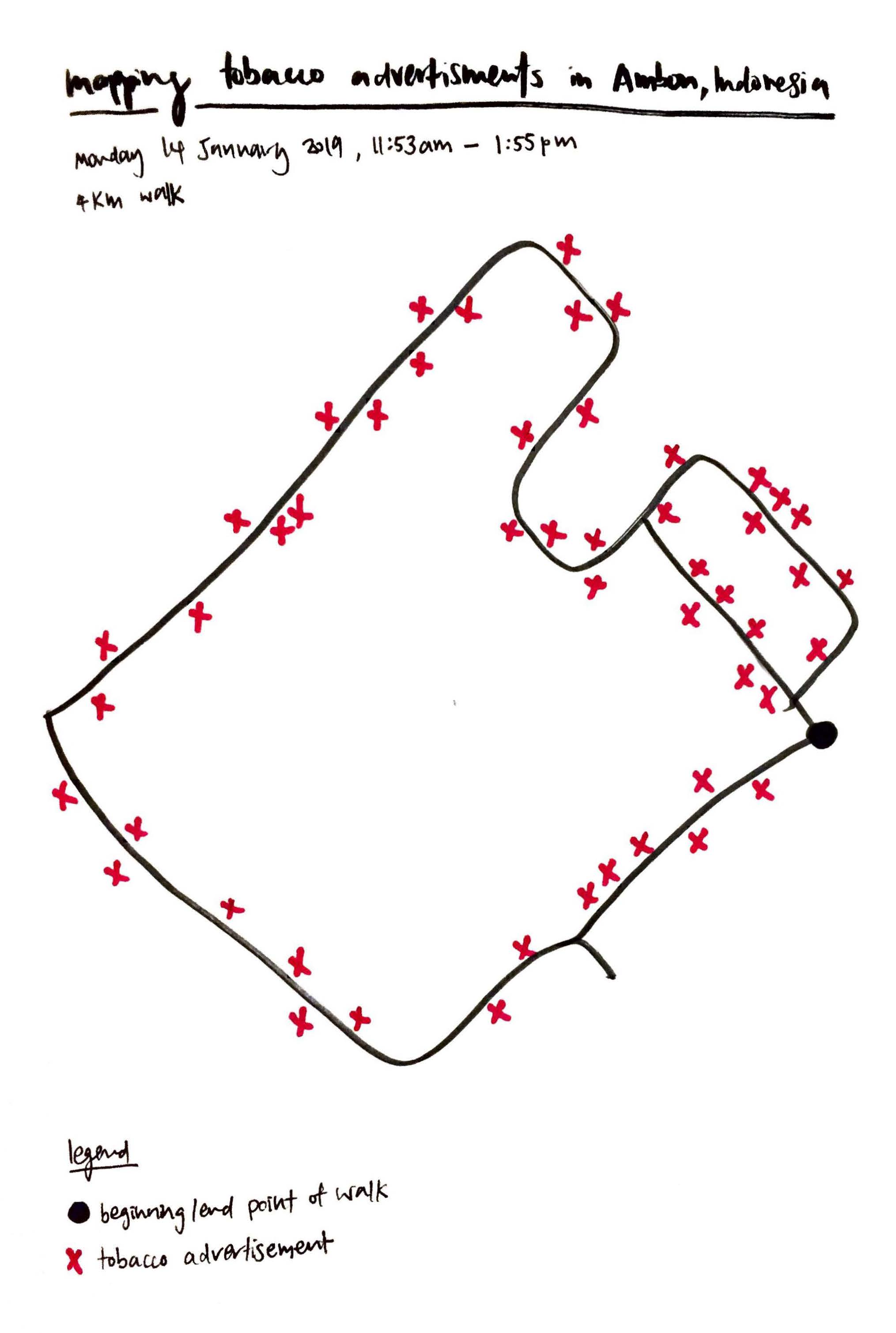

On a short walk around Ambon – through quiet residential areas, the bustling market, and busy main roads – it is quickly evident that one can barely walk a few metres without seeing cigarette advertisements plastered on cloth banners, wall posters or big billboards (Nichter et al. 2009).

Photographs taken during a walk around Ambon, Indonesia

The frequency in which these tobacco advertisements appear is appalling, and Indonesia’s alarming smoking statistics can in part be attributed to the aggressive and innovative cigarette marketing prevalent in Ambon and other parts of Indonesia (Nichter et al. 2009). In the city of Yogyakarta in Central Java, tobacco billboards are displayed prominently, and most small kiosks and shops are covered with tobacco advertisements – which concurs with the advertising landscape in Ambon as well, as seen from the images above (Nichter et al. 2009). Similarly, in Denpasar, Bali, it was found that 7 out of 10 retailers displayed at least one banner promoting cigarette products (Astuti & Freeman 2018). The combination of persistent advertising and readily available and affordable cigarettes, among other social and cultural factors, has resulted in over 62% of Indonesian males smoking regularly, and boys as young as 10-years-old beginning to smoke (Achadi, Soerojo & Barber 2005).

Although the dense saturation of tobacco advertising in Indonesia is shocking to witness, the most worrying aspect, however, is how these advertisements are seamlessly integrated into the Indonesian landscape and tobacco becomes synonymous with Indonesian culture. As a foreigner visiting Indonesia for the first time and experiencing culture shock from being bombarded with tobacco advertising, the imagery and slogans have started to blend into the environment and I have begun to accept that tobacco culture is a norm in Indonesia. Considering my own firsthand experience, I could only imagine that the local Indonesians have also accepted tobacco as a normality and are not fazed by the saturation of tobacco advertisements – tobacco is so deeply engrained in the fabric of Indonesian culture that the advertisements seemingly belong in front of houses and kiosk shops. Indigenous cigarette advertising exploits and manipulates Indonesian cultural values to promote smoking, and when published en masse, can create a natural association between desirable lifestyle attributes and tobacco – cultivating beliefs and habits in favour of tobacco that has proven, and will continue, to be extremely difficult to alter (Reynolds 1999).

References:

Achadi, A., Soerojo, W. & Barber, S. 2005, ‘The relevance and prospects of advancing tobacco control in Indonesia’, Health Policy, vol. 72, no. 3, pp. 333-349.

Astuti, P. & Freeman, B. 2018, Protecting young Indonesian hearts from tobacco, The Conversation, viewed 20 January 2019, <https://theconversation.com/protecting-young-indonesian-hearts-from-tobacco-97554?fbclid=IwAR1cOwtSijNbCAgT4NrZf0Q2CxfiSWZC1lO3iQesk_umTe5AwkDb2hCNKSA>.

Nichter, M., Padmawati, S., Danardono, M., Ng, N., Prabandari, Y. & Nichter, M. 2009, ‘Reading culture from tobacco advertisements in Indonesia’, Tobacco Control, vol. 18, pp. 98-107.

Reynolds, C. 1999, ‘Tobacco advertising in Indonesia: “the defining characteristics for success”’, Tobacco Control, vol. 8, pp. 85-88.

Ambon, Indonesia

Ambon, Indonesia